TRUMP LIKES IT THAT WAY.

I remember the mine at El Estor on the shores of Lago Isabel for many decades,iy was considered Canadian but was probably international Jewish controlled all along.It appears the Bronstein's are just part of the internatuonal Elders of Zion that the Jewish controlled media assures us is a myth.And of course Jes are not Jews at all but white people from Russia and East European origen.Isreal prpvided the Galil rifles whose bullets were in everybody dead body shot by Israeli controled Guatemala military in the 1980's.

The company was co-founded by Aleksandr Bronstein, an Estonian,(Jewish Zionist), entrepreneur, and his son Daniel, who is a German citizen.

Mar 18, 2010 - Arkady Gaydamak, President of the Congress of Jewish Religious Communities ... Farida Gainullina, Russian Federation State Duma Labor and Social ... But the well-known oligarch, Alexander Bronstein who owned the company ... has been one of the captains of domestic business - Alexander Bronstein.

Solway reports its headquarters are in Larnaca, Cyprus. The website gives a telephone number which is not answered, and an email address which bounces. Cyprus company registrations reveal the Cyprus entity is owned by an entity registered elsewhere, but not identified. Russian press reports claim that one of the prominent shareholders is Boris Birshtein, a Russian-speaker with a controversial business record. He emigrated in the Soviet period, and holds Canadian and possibly Israeli citizenship. He lists his home office in Toronto, but doesn’t respond to questions there.

Left: Birshtein with Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu; right: Birshtein with former Canadian prime minister Jean Chretien

A published list of Solway directors doesn’t mention Birshtein. Birshtein doesn’t mention Solway in his list of company affiliations. A spokesman for Solway in Moscow, who declined to be quoted by name, is emphatic that the Solway shareholders are EU citizens, and that Birshtein has had no relationship to Solway.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-06-20-forbidden-stories-a-damning-photo-holds-a-swiss-russian-mine-accountable-in-guatemala/

The company fishermen blame for their worry is Solway, a Swiss group originally operating in Russia with a holding company in Malta. It arrived in El Estor – a remote municipality hidden in the middle of mountains and hills – back in 2011 to take over a ferronickel mine named the Fenix Project, selling the alloy of iron and nickel internationally to various steel manufacturing companies......

https://www.thestar.com/news/investigations/2019/06/19/this-photo-of-a-dead-fisherman-left-many-questions-for-a-swiss-russian-mine-in-guatemala.html

A group of fishermen from an Indigenous community in Guatemala demanded to know more about the environmental impact of a ferronickel mine established on their ancestral land. One of them was killed, and a local reporter was criminalized for covering the story.

Forbidden Stories, an international consortium of 40 journalists publishing in 30 media organizations around the world, joined forces to continue the reporter’s work. This is part of the “Green Blood” series, a project pursuing stories of journalists who have been threatened, jailed or killed while investigating environmental issues.

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jun/19/european-owned-mine-paid-guatemala-just-1-4m-in-compulsory-royalty-taxes

The opencast Fenix mine belongs to the Bronstein family and is run by their Swiss-based Solway group. Solway benefits from Guatemala’s low nickel royalty rate, which is calculated at just 1% of all the revenues made from selling the unrefined ore it digs out of the ground. Recent proposals to increase rates to 15% were not implemented.

Solway’s extraction business, Compañía Guatemalteca de Níquel (CGN), digs the ore out of the ground. Its sister company, Pronico, also owned by Solway, operates a refinery at the Fenix site, and after buying the ore from CGN, turns it into ferronickel.

CGN is the company that pays the compulsory royalty tax. The price at which it sells to Pronico determines its revenues, and therefore how much the Guatemalan treasury receives...........

An analysis of Solway’s filings with the country’s mining ministry helps to explain why its contribution is so low......

https://www.bnamericas.com/en/news/mining/guatemala-mulls-25-mining-royalty

http://johnhelmer.net/mayans-fight-conquistadors-over-guatemalan-nickel-mine-russian-foreign-ministry-backs-cyprus-company/

By John Helmer, Moscow

What to do if you are a Russian mining company with a billion dollars’ worth of asset exposure securing large debts, and your chain of production is struck at start and finish by corruption scandals, international litigation, popular protest, collapse of government authority, and homicidal violence? The solution is to pretend to your bankers you aren’t Russian — and privately beg the Kremlin for help.

That is what the Solway Group of companies has been doing at its nickel mine in central Guatemala, and at its ferronickel refinery in southeast Ukraine. Asked about Solway’s Russian roots by a Ukrainian reporter last month, Solway’s chief executive Daniel Bronstein replied that “Solway Investment Group is a Cyprus-based international industrial group with a 100% EU capital and operational offices in Luxemburg, Switzerland and Estonia.”

At almost the same time, a Russian source in Guatemala City said the Russian Ambassador, Nikolai Babich, had been to see the President of Guatemala, Otto Molina, to ask for his intervention on behalf of the mine’s Russian management and the Solway owners.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (below, left) met with Molina (right) on March 26, but there is no record in the ministry communiques that the two of them discussed the Fenix mine and the security of the Russian investments there.

Solway bought into Guatemala in 2011. In 2013 Director of the Latin American Department of the Russian Foreign Ministry Alexander Schetinin noted that the Guatemalan government had formalized the license for Solway to operate through [Compañía] Guatemalteca de Niquel [CGN] “with Russian participation. We hope that now the logical step would be signing in the near future bilateral agreements on investment promotion and protection; actually we are ready to agree, it will be this year.” The agreement was signed on November 27, 2013. The Russian and Guatemalan foreign ministers have endorsed the agreement as “a fundamental tool for ensuring the growth of the volume of trade exchanges and investments between the two countries”, but it has yet to be ratified.

Ambassador Babich (right) met with President Molina late last year and discussed Solway’s concerns to protect its mine from local Guatemalan protests, land claims by the indigenous Mayas of the area, and allegations regarding the mysterious deaths of three university students in the mine area in 2012. Since then the Guatemalans have begun organizing protests to disrupt the movement of Solway’s trucks carrying ore from the mine to the port of Santo Tomas de Castilla. A delegation of Guatemalans is due in Canada this month to support claims against the mining company’s former Canadian owner for murder, rape, and loss of homes and land.

Ambassador Babich (right) met with President Molina late last year and discussed Solway’s concerns to protect its mine from local Guatemalan protests, land claims by the indigenous Mayas of the area, and allegations regarding the mysterious deaths of three university students in the mine area in 2012. Since then the Guatemalans have begun organizing protests to disrupt the movement of Solway’s trucks carrying ore from the mine to the port of Santo Tomas de Castilla. A delegation of Guatemalans is due in Canada this month to support claims against the mining company’s former Canadian owner for murder, rape, and loss of homes and land.

Russian Embassy officials are hostile towards the protests of local residents against the Fenix mine, and openly take the side of Solway and its Russian employees, although Solway’s Cyprus registration is acknowledged. It is estimated that there are 150 Russian nationals in Guatemala working for Solway and its local mining company. The Embassy is assisting them individually, and also the company, though this is not acknowledged publicly because the company is not officially Russian. The Embassy claims it doesn’t know who Solway’s shareholders are.

Solway reports its headquarters are in Larnaca, Cyprus. The website gives a telephone number which is not answered, and an email address which bounces. Cyprus company registrations reveal the Cyprus entity is owned by an entity registered elsewhere, but not identified. Russian press reports claim that one of the prominent shareholders is Boris Birshtein, a Russian-speaker with a controversial business record. He emigrated in the Soviet period, and holds Canadian and possibly Israeli citizenship. He lists his home office in Toronto, but doesn’t respond to questions there.

Left: Birshtein with Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu; right: Birshtein with former Canadian prime minister Jean Chretien

A published list of Solway directors doesn’t mention Birshtein. Birshtein doesn’t mention Solway in his list of company affiliations. A spokesman for Solway in Moscow, who declined to be quoted by name, is emphatic that the Solway shareholders are EU citizens, and that Birshtein has had no relationship to Solway.

On the Solway list there are two members of the Bronstein family, Alexander and Daniel. On a Guatemalan Government visit to London last year, Bronstein junior was listed on the Guatemalan side as Solway’s chief executive. He reports education at British schools and employment with the Swiss-American investment bank Warburg Dillon Read, before he moved to Solway. Solway said this week he holds an EU passport.

Another name on the Solway board of directors is Mikhail Lipkin, who is a US citizen and US resident with a controversial public record. The New York Times reported a summary in September 1997. Here is the 9-year old US Securities and Exchange Commission dossier, identifying Lipkin as a resident of Marlboro, New Jersey, and accusing him of stock fraud. The record continues in New Jersey and gets more controversial.

Andre Seidelsohn is another of the Solway directors; he appears to be based in Estonia. Click this, and then his name, to open the record of Seidelsohn’s company associations.

In last month’s Ukrainian press interview, Daniel Bronstein explained that his family had owned an aluminium smelter in Volgograd, and when it was sold, invested the proceeds offshore. “We started reinvesting money gained from the aluminum deal into ferronickel production all over the world including Ukraine. In 2003 we purchased corporate rights on Pobuzhskiy Ferronickel Plant (PFP) that had been bankrupted by the previous owner. ..We purchased the plant and invested over USD 100 million into modernizing the processing technology for adjusting it to the imported ore, with the higher percentage of Nickel. In 2004 the plant was restarted at its full capacity and hasn’t stopped since.”

In last month’s Ukrainian press interview, Daniel Bronstein explained that his family had owned an aluminium smelter in Volgograd, and when it was sold, invested the proceeds offshore. “We started reinvesting money gained from the aluminum deal into ferronickel production all over the world including Ukraine. In 2003 we purchased corporate rights on Pobuzhskiy Ferronickel Plant (PFP) that had been bankrupted by the previous owner. ..We purchased the plant and invested over USD 100 million into modernizing the processing technology for adjusting it to the imported ore, with the higher percentage of Nickel. In 2004 the plant was restarted at its full capacity and hasn’t stopped since.”

The Solway website reports the group had also owned stakes in the Kluchevsky Ferroalloys Plant and the Red October Steel Plant in Volgograd, before selling out. The Volgograd steel story can be read here.

According to Bronstein, he and Solway said sayonara to Russia more than a decade ago. “At the end of 1990s –early 2000s there were great possibilities in Russia. Today, after consolidating all our assets in base metals and ferronickel, we can see more profits in the western countries.”

A rating agency report implies that in 2013 Solway returned to Russia to raise finance by selling bonds. Solway told Fitch that in 2012 it had revenues of $557 million, and earnings of $119 million. The breakdown of production value, according to Fitch, was ferronickel concentrate (67% of revenues in 2012), copper and copper concentrate (14%), lead concentrate (11%), and zinc concentrate (5%).

What is revealed thereby is that two-thirds of Solway’s revenues depend on the Guatemalan mine and the Ukrainian refinery. According to Fitch, there is transfer pricing between the two. “Fitch notes that transactions with related parties account for a significant share of revenue. The Agency considers the relatively low level of transparency in Solway one of the factors constraining the ratings.”

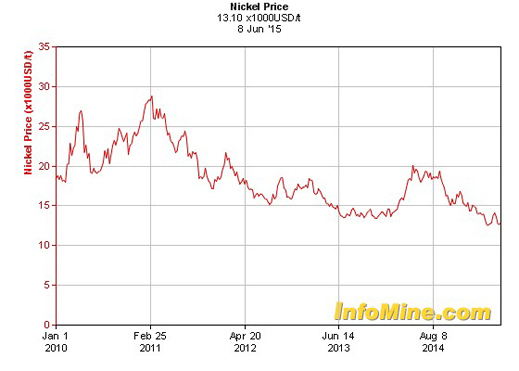

Solway was coy with Fitch in disclosing its debt, but forecast “deleveraging” to start in 2014 and continue into this year. Since the Fitch report, the nickel price has fallen sharply. It is now half of what it was when Solway moved into Guatemala:

In 2014, the Ukrainian refinery was cut off from its feedstock from Indonesia after the government in Djakarta banned export of unprocessed nickel ore. “If we did not have a project in Guatemala,” concedes Bronstein, “we would have stopped the plant in Ukraine. It is nearly impossible to find ore on the world market.” Guatemalan export figures indicate there was a surge of ore shipments in 2014 when the value jumped tenfold to $55 million.

Ukrainian reports reveal that in 2013 Pobuzhskiy turned out 21,184 tonnes of nickel product. In 2014, the total was down 12% to 18,615 tonnes. Although the plant is well to the west of the fighting in the Donbass, the civil war has caused a dramatic drop in electricity to power the refinery. The International Monetary Fund programme for Ukraine has raised the price of electricity by 28%, while the collapse of the central government’s budget and the loss of Donbass-region coal and other power sources have cut electricity supply. So nickel output is forecast to fall again. Solway says its 2014 nickel production should have been 37,000 tonnes. It claims it is targeting a rapid rate of growth — 37,000 tonnes this year; 86,000 tonnes in 2016; and 120,130 tonnes in 2017.

According to Bronstein last month, “due to the latest political and economical events banks hardly consider any capital investments in Ukraine. Even financing trade deals is ranked as highly risky investments. At the same time our production process is very long. It starts with loading the ships with raw ore in South America and ends months later with delivering the final product to the customer. Meanwhile we still have to pay for delivering, processing etc. and this needs to be credited. None of the banks is ready to support Ukrainian businesses nowadays.” In its pitch for fresh western loans, Pobuzhskiy claims: “100% of the share capital is owned by EU citizens.”

Solway releases claim it has invested more than $500 million in Guatemala, and is promising to invest more than a billion dollars. If it can expand its Guatemalan nickel refinery, this will offset the trouble in the Ukraine. But trouble now threatens Solway in Guatemala.

Today Solway released a summary of its results for 2014. The group says it lifted sales revenues by 3.3% over 2013 to $532 million, while reduced costs lifted earnings by 29.4% to $120 million. Net debt, the group says, was $132 million. The numbers don’t appear to be much better than those reported by Fitch for 2012.

The new report explains “the increase in revenue was primarily generated by the company’s ferronickel development, in particular the successful commissioning of the Fenix Project in Guatemala… In 2015 Solway plans to complete its ramp-up phase and reach 25,000 metric tons of annual nickel production. Further expansion at Fenix during Phase 3 could potentially drive production capacity up to 50,000 metric tons. Since acquiring Fenix in 2011, the Group has invested 530 million USD in the asset.”

The Fenix (Phoenix in English) mine in central Guatemala has been the site of conflict for decades. Initial production by a Canadian mining concern lasted for just four years before the mine was shut down in 1981. Until the Solway takeover in 2011, the Mayan Q’eqchi’ had been driven off their traditional land and forcibly resettled. As Canadian mining companies battled indigenous claims to the land and opposition to evictions, there was police violence, murder, rape, and environmental damage from the mining. For this noone in Guatemala blamed Solway or the Russians when they took over.

The sale and purchase agreement between Hudson Bay Minerals and Solway indemnified Solway from what had already happened, and HudBay accepted legal liability. The Canadian courts have ruled that the Mayans are eligible to sue HudBay, and their claims are proceeding. The Toronto law firm Klippensteins is representingthem.

At the moment the mine site comprises both a pile of ore already excavated from the earlier, abandoned operations, and a new strip mine. The ore is trucked east to the new port of Santo Tomas de Castilla, indicated on the map at the older port of Puerto Barrios.

Solway arrived in September 2011, when HudBay, a listed Canadian miner, sold out. HudBay had paid $400 million earlier, but then decided it could not afford to risk an estimated billion-dollar in the investment required to make the Fenix mining operation profitable. The Canadians exited before nickel had peaked in price.

Solway paid $140 million in cash, and a promise of $30 million in royalties to come. HudBay’s financial report for 2011 says it had written down the value of Fenix by $212 million from its acquisition price. Solway thought it was getting a bargain.

A Russian by the name of Dmitry Kudryakov is the chief executive of the mine and of the local mining company Solway owns – Compañía Guatemalteca de Níquel (CGN). He immediately promised to invest $1.6 billion in the mine, and bring annual ore production up to 150,000 tonnes. In July last year, he and Guatemalan officials inaugurated a new ore-processing plant.

Kudryakov claimed at the time that the mine company was producing 25,000 tonnes of nickel, which it was exporting; employing 1,500 people; and representing value of “US$470 million of foreign exchange and US $50 million annually to the treasury in taxes and royalties.” It is unclear how these numbers have been calculated. Telephone and emailed questions to Kudryakov at CGN have gone unanswered.

Local and Canadian sources report that Solway and CGN have run into several problems. In 2012 three university students on an environmental biology field trip mysteriously died on CGN land. There are calls for an independent investigation, and for the mining company to accept liability. Also, there has been violence between CGN’s security force and what local sources describe as a “narco gang”, which demanded control over the trucking contract for ore deliveries to port. Local sources say the gang got what they asked for. This in turn has aroused suspicion that there is more to the cargoes leaving Guatemala than 2%-grade nickel bearing ore bound for Pobuzhskiy.

Referring to Guatemala’s drug production and trade, a Canadian source said the remote area surrounding the mine “is a well-known narcotics region.” Russian officials meeting their Guatemalan counterparts have referred several times to the priority they share in combatting drug trafficking. Following Lavrov’s March 26 meetings in Guatemala, the Russian Foreign Ministry announced the Russian plan to “develop cooperation between law enforcement agencies. Representatives of the National Police of Guatemala undergo professional training in Russia, taking an active part in the ongoing Russian Federal Drug Control Service in Nicaragua regional courses for training and staff development of anti-drug services of the countries of Central America. We hope to continue this cooperation.”

This year protests by the Maya against Solway’s mine operations have intensified. The sizeable number of Russians who are employed by CGN are isolated in a guarded compound outside the town of El Estor, avoiding local contact for fear of clashes. Local sources claim road blockades of the mine truck route have begun.

In the capital, President Molina, a former general, announced on May 21 the replacement of his ministers for environment, energy and mines, and interior, following disclosure of evidence of high-level corruption linked to mine permits and the ore and minerals trade. His action followed the resignation of his Vice President, Roxana Baldetti, on May 8 “Not since 1944,” says a Guatemalan source, “has there been such an outpouring of disgust for the authorities, both political and economic. May 30 was the most recent general nationwide mobilization. Another is planned for June 11. Demands include that the government step down; that a constituent assembly be established to set up a multicultural, multilingual federation of autonomous Maya territories. A liberation movement has begun.”

Last week, Francisco Palomo, a well-known pro-government lawyer, was assassinated in a Guatemala City street (right). National elections for the presidency and parliament are due on September 6. Molina has already served one term, and is constitutionally barred from running again.

Last week, Francisco Palomo, a well-known pro-government lawyer, was assassinated in a Guatemala City street (right). National elections for the presidency and parliament are due on September 6. Molina has already served one term, and is constitutionally barred from running again.

In Moscow a source at Norilsk Nickel, the global leader in nickel production, said he is sceptical of the Canadian and Guatemalan belief that Russian investors are behind the Fenix mine. “It was a small project. Solway needed laterite materials for their production of ferronickel. They looked initially at a project in Indonesia. Then Indonesia imposed an embargo on the export of raw materials. [Solway] first thought to build a plant for processing [nickel ore] in Indonesia, then abandoned the idea and began to consider Guatemala. The project is high cost. Any laterite project has an unpredictable cost.” The source says he cannot estimate how cost-effective Solway’s Fenix is in today’s low nickel market. He acknowledges that to feed the Ukraine plant, Solway has calculated it doesn’t have much choice after the Indonesian embargo.

“I had understood they would flip it”, said a Canadian source of Solway’s original intention for Fenix. “Unless the mining project is more than meets the eye. The Fenix mine site is in a very remote area of central Guatemala. What else can you do there? It’s difficult to counter HudBay’s calculation that a billion-dollar investment won’t be profitable.”

Solway counters that Guatemala’s cost of production can be kept down to a level that will remain profitable at current or anticipated prices on the nickel market. It is also betting that electricity costs in Guatemala will not rise at the speed of Ukrainian power rates. “The corporate strategic goal,” according to Solway’s statement this week, is “to enter the world’s top ten producers of nickel. In 2015 Solway plans to complete its ramp-up phase and reach 25,000 metric tons of annual nickel production. Further expansion at Fenix during Phase 3 could potentially drive production capacity up to 50,000 metric tons.”

Bronstein adds: “Despite difficult market conditions, 2014 was marked by considerable improvement in results, particularly reduction of the debt level and a sharp growth in EBITDA compared to 2013. Completion of the ProNiCo nickel smelter in Guatemala and launch of the gold production facility at Island of Urup, a part of the Group’s KurilGeo Project, are the highlights of a year of progress at Solway. These achievements mark significant milestones on the way to implementing The Group’s strategic goal – to become one of the world’s top metal producers.

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/investigations/2019/06/19/this-photo-of-a-dead-fisherman-left-many-questions-for-a-swiss-russian-mine-in-guatemala/cristina_maaz_1.jpg)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/investigations/2019/06/19/this-photo-of-a-dead-fisherman-left-many-questions-for-a-swiss-russian-mine-in-guatemala/_1_carlos_maaz.jpg)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/investigations/2019/06/19/this-photo-of-a-dead-fisherman-left-many-questions-for-a-swiss-russian-mine-in-guatemala/mine_1.jpg)

/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/news/investigations/2019/06/19/this-photo-of-a-dead-fisherman-left-many-questions-for-a-swiss-russian-mine-in-guatemala/the_fenix_project_1.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment